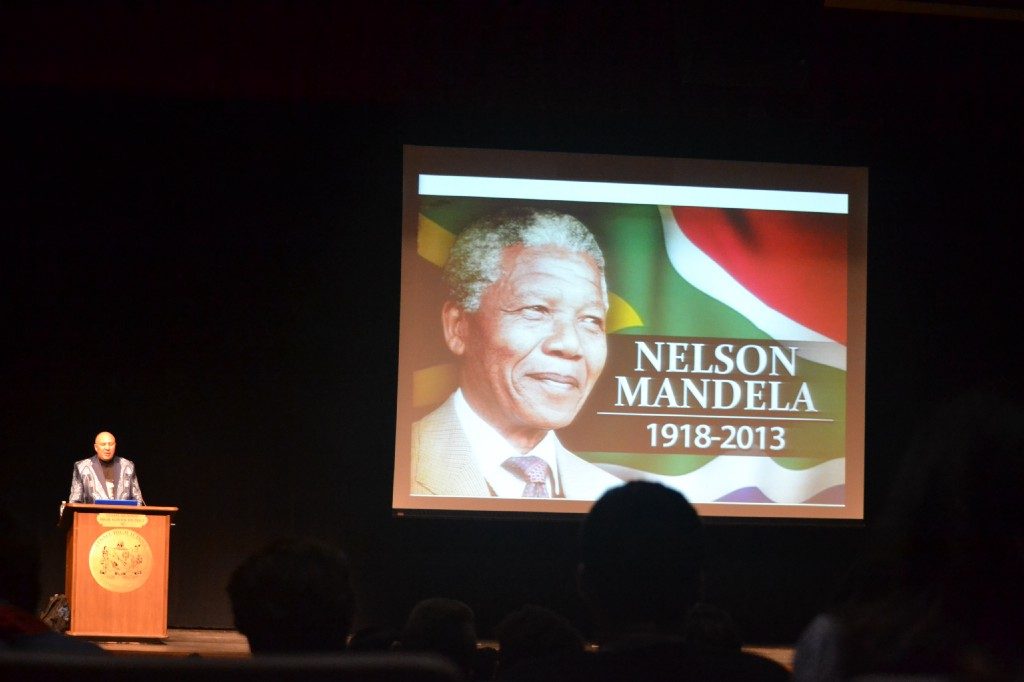

The Lenape Regional High School District met living history this week with a visit from Chris Lubbe, former bodyguard to Nelson Mandela.

The Lenape Regional High School District got to meet a part of living history this week when Chris Lubbe, former bodyguard to Nelson Mandela, spoke at Lenape High School as part of New Jersey’s annual “Week of Respect.”

As mandated by the state’s anti-bullying legislation, school districts across New Jersey observe the Week of Respect by providing lessons related to the prevention of harassment, intimidation or bullying.

For some local students, part of those lessons involved listening to a man who spent eight years of his life guarding the revolutionary who led the emancipation of South Africa from the white-minority rule of apartheid and served as the country’s first black president from 1994 through 1999.

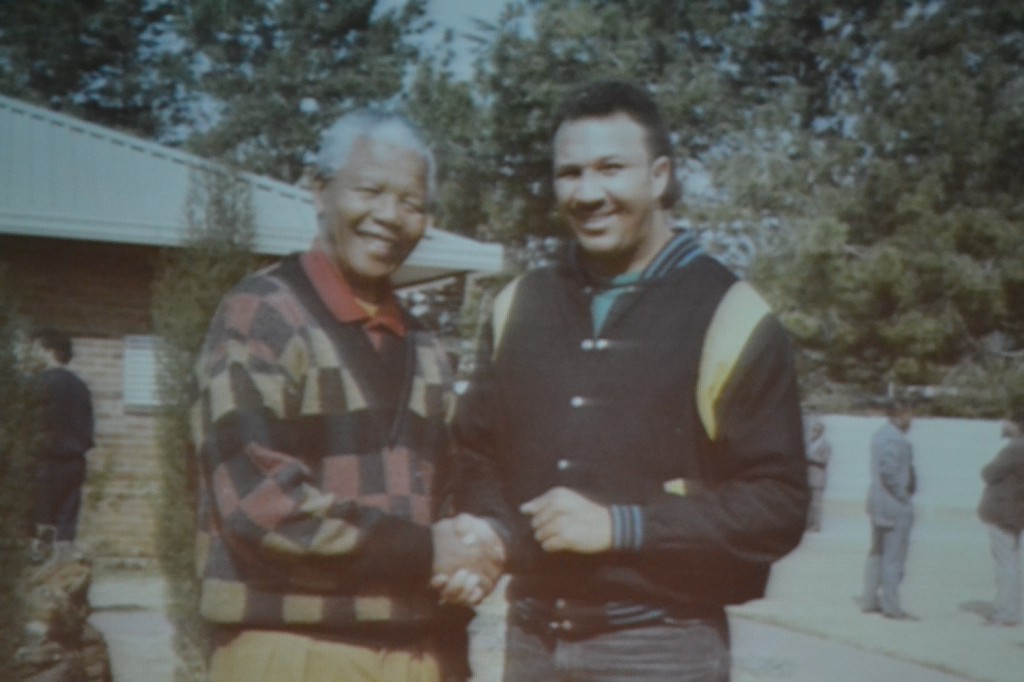

While Mandela was a hero to Lubbe during his time growing up in South Africa, it was only by chance he met the anti-apartheid activist in the early 1990s when Mandela had asked to meet the person (Lubbe) in charge of IT for a music concert for the African National Congress.

When Mandela laid eyes on Lubbe, who stands 6’3” with a size 14 shoe, Lubbe recalled Mandela saying “you’re just the man I need,” as Mandela offered him a position as one of his bodyguards in what Lubbe described as one of the shortest job interviews he’s ever had.

As this year would have marked Mandela’s 100th birthday, Lubbe has been speaking to groups about his time guarding Mandela, as well as the life he and his family faced because of the color of their skin while growing up in a shantytown in Durban, South Africa, during the peak of apartheid.

This week Lubbe spoke to students of a world with no voting rights, no jury systems, separate areas to live, separate classes of jobs, separate schools, separate buses, separate train coaches, separate bridges, separate parking, separate beaches and much more.

Even the right of Lubbe’s family to raise him as their own was originally in question, as, due to the rape of his maternal grandmother by a white man, registration officials didn’t believe the lighter color of Lubbe’s skin matched that of his family.

As a child, Lubbe said officials actually measured the thickness of his lips and the width of his nose, as well as seeing if his curly hair could hold a pencil, in attempts to properly classify him as “white” or “colored.”

Lubbe said he was about 9 years old when he first heard that story.

“I imagined there was a person called apartheid — I couldn’t quite understand that it was a system. I would hear people talking about apartheid as if it was some evil person, and I couldn’t believe my entire existence was determined by a pencil.”

Lubbe also shared other stories, such as the time his diabetic mother fell ill on a segregated bus when the two were travelling, and the bus couldn’t stop until they had traveled out of an area that was meant for whites only.

However, once off the bus, Lubbe’s mother was placed a bench meant for whites only, from which two police officers shoved her off without a word, causing her smash her head on the ground and fall into a coma for several months.

Yet Lubbe’s thirst for knowledge about his identify and his thirst for knowledge in general only grew throughout his childhood.

Since his schooling consisted of a single classroom with one teacher and 60 students, Lubbe had to search elsewhere for information, including visiting the nearby dump as a child to pick through trash for books.

Lubbe was in high school when he began helping to organize peaceful marches against apartheid, often facing tear gas and bullets from the police. He was 14 years old when he was first arrested for leading a march, and it was during a three-month prison sentence when he was first tortured through waterboarding.

Yet upon his release, Lubbe’s activism continued, and after graduating high school he was eventually arrested once again and sentenced to time in prison for organizing peaceful marches.

Again, he was waterboarded, kept without food, forced to stand under cold showers and subjected to other physical and mental punishment.

Lubbe would later be forced to work with his torturer while guarding Mandela during Mandela’s presidency, and while he originally thought of using his gun for revenge, he knew Mandela would not have it.

“He believed, if you took revenge, that would be too easy. He believed reaching out would be the better option,” Lubbe said.

Lubbe eventually forgave his torturer, and the two later became best friends.

In his speech to students this week, Lubbe also spoke of the Zulu greeting “Sawubona,” which translates to “I see you,” and its basis in the African principal of “Ubuntu” that relates to how human beings are connected to one another.

Lubbe said Mandela also spoke to him about “Ubuntu.”

“Our humanity can only be defined through our interaction with each other … until you say ‘Sawubona’ to someone, you don’t’ bring them to life,” Lubbe said. “It’s a beautiful word.”