When acting New Jersey Gov. James F. Fielder took a trip to Burlington County in 1913, it wasn’t to recognize the lush Pine forests, hardworking homesteaders or rural charm.

Instead, Fielder told one newspaper that “the state must segregate and sterilize these people.” He ran — and won — on that platform, allowing him to serve for another three years.

“It’s a very dark history,” said William J. Lewis, author of “New Jersey’s Lost Piney Culture.”

During his term, Fielder set up state-funded psychiatric hospitals throughout South Jersey. He used an “intelligence test” created by Henry Goddard, a psychologist who coined the term “moron” to justify his acts against Pineys. Goddard’s test was later used in Nazi Germany.

Older generations may remember their parents warning them to be alert during drives to the Shore, out of fear of “degenerate” Pineys, Lewis said.

“But there was a culture and a history of hardworking people that was never really told,” he explained. “They hadn’t gotten the respect that they deserve.”

Lewis, who also runs the Facebook page Piney Tribe, has made it his mission to educate people about the negative stereotypes Pinelands residents have faced for hundreds of years. They were integral to the economy because they ran mills, harvested goods and more. South Jersey was the center of the dry floral industry, Lewis added, a lucrative business that served shops in nearby metropolitan areas like Philadelphia and New York City.

When the government preserved the Pines, many residents were forced to abandon their off-the-grid lifestyle and assimilate to a more suburban way of life.

“Federal properties became off limits for picking and pulling any plants, which then made that job of yours that put food on the table illegal,” Lewis noted. “You became an outlaw when you would do it.”

Constant policy admonishing the Piney way of life caused much of the traditional culture to be lost. Lewis is working on new books combating that by recording Piney words for local flora and fauna that were replaced by scientific Latin names.

“When those new terms came out, they did away with the connection the local people had to the plants that were in their neighborhoods,” he said. “Whole cultures and traditions were tied to those plants.”

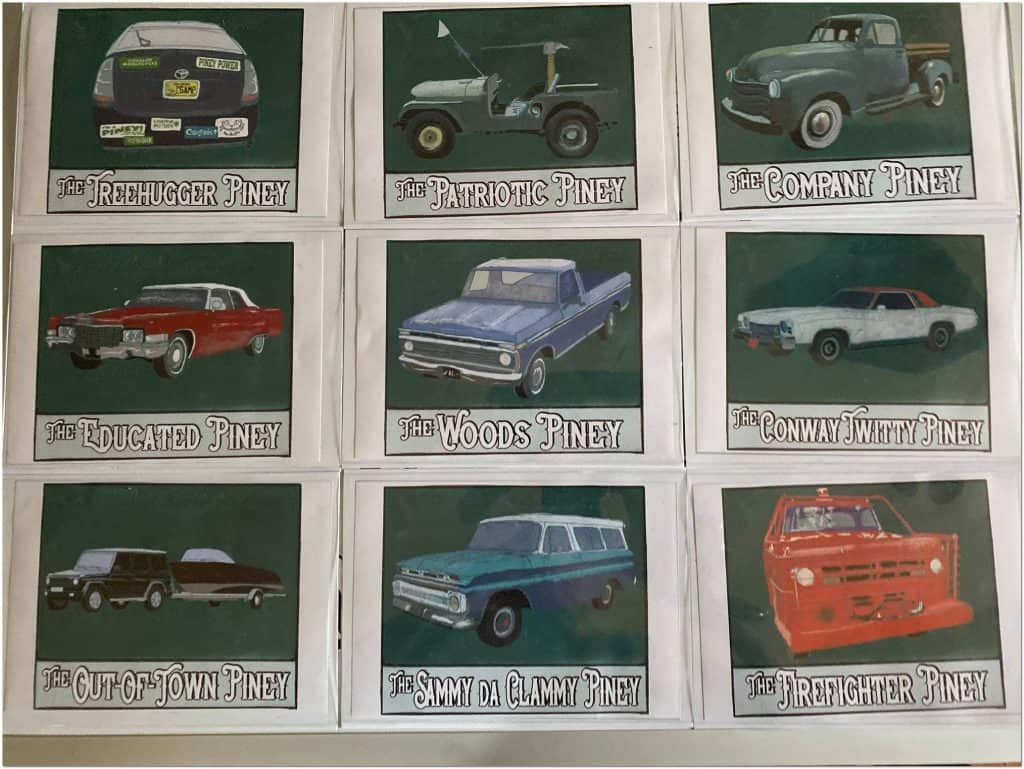

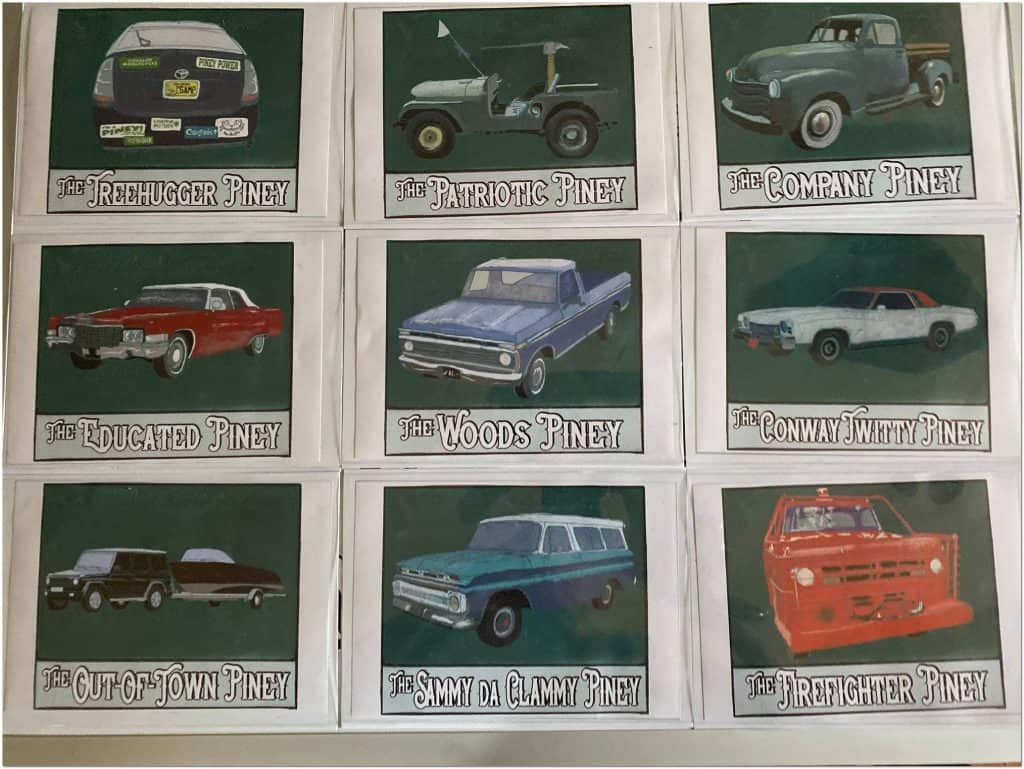

Lewis also hopes to explain the diversity in Pineys that comes from 52 different municipalities with varied terrains. Some residents made their livelihoods on the beach, while others are traditionally hunters or gatherers.

Lewis wants all residents, whether or not their families grew up in the Pine Barrens, to feel a part of the Piney community.

“I really want to give people license to be able to use that term,” he stated. “Even if they’re first generation, they can still be proud to be a Piney.”

That sentiment is something Lewis finds integral to protecting Piney culture.

“To have the culture live on, you have to recognize the culture’s impact in New Jersey’s tapestry,” the author said. “But you also have to give people the license to say, ‘I’m a different type of Piney, but I love this place and I want to protect it.’”