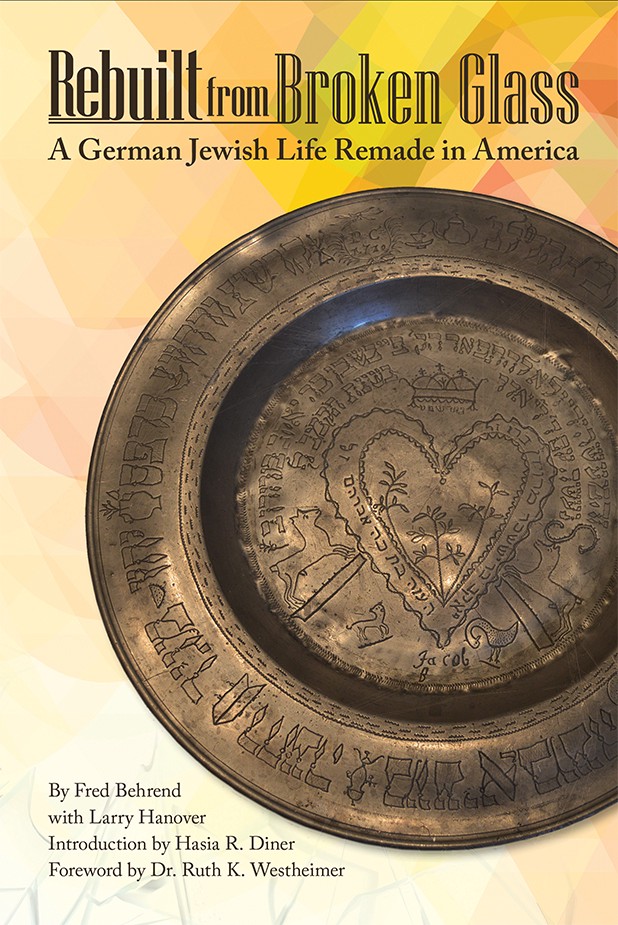

Voorhees resident Fred Behrend, 90, talks about his family’s escape from Nazi Germany and starting a new life in the United States in his new book, “Rebuilt from Broken Glass: A German Jewish Life Remade in America.”

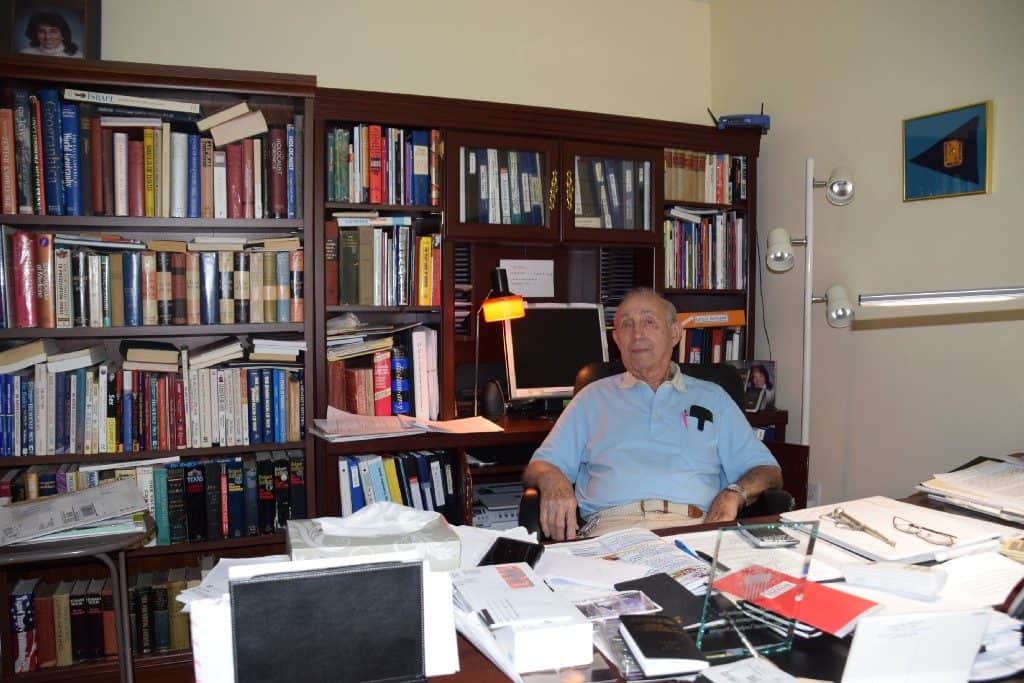

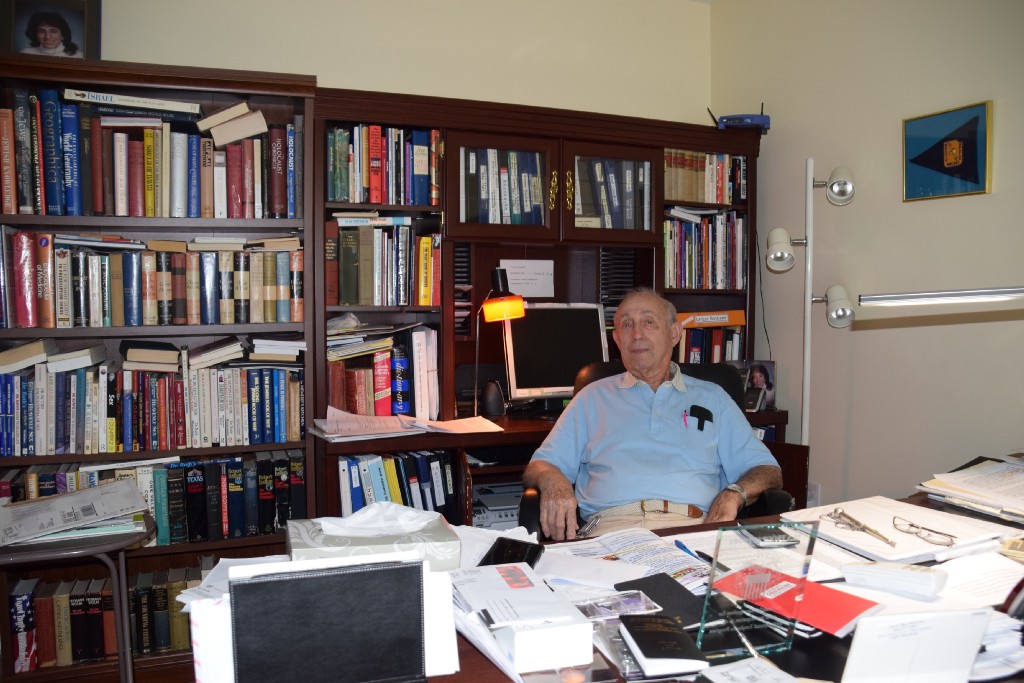

Walking into Fred Behrend’s home office is like walking into a history museum.

The 90-year-old Voorhees resident has diaries from his descendants dating all the way back to the 16th century. Hundreds of pages of his family history sit crammed on the bookshelves and inside the drawers of his desk.

Behrend has contributed a lot to these archives himself. As a Jewish child living in Germany in 1930s, he watched as the Nazis came to power and snatched away everything he had. He lived through Kristallnacht, a night in 1938 where the Nazis burned down Jewish synagogues, schools, places of business and homes. He remembers how he and members of his family escaped the Holocaust through Cuba and eventually gained admittance to the United States, with no money to their name. It was in America where Behrend overcame the odds to become a successful businessman.

Behrend recalls many of his experiences like they happened yesterday. Now, his experiences will be available for all to read. Larry Hanover, a Cherry Hill resident and former newspaper reporter, teamed with Behrend to co-author his memoir, entitled “Rebuilt from Broken Glass: A German Jewish Life Remade in America.” The memoir, which includes just some of Behrend’s many lifelong memories, was released on July 15.

Compiling decades of memories

Hanover vividly remembers the first time in 2010 he heard Behrend speak about his life.

“I was out of journalism,” Hanover said. “I had been with the Trenton Times for 18 years and then I was with the Courier-Post for a little under a year. I had been out for a few years. I had colleagues who said I should write a book.”

Hanover was attending an event at Congregation Beth El, the synagogue both he and Behrend are members of. Behrend was speaking to a group of high school students and their parents. Hanover was in attendance and Behrend immediately captivated him with his memories and storytelling.

Behrend said writing a book was something he never considered prior to meeting Hanover.

“(Hanover) came up to me and said, ‘You know, you have so many interesting stories there, have you ever thought of writing a book,’” Behrend said. “I said I’m not a writer.”

Hanover was able to convince Behrend to work with him, and the two began compiling stories for a memoir.

The book took seven years to put together. Hanover sat for hours in Behrend’s home, recording story after story from Behrend’s life.

“There’s very few left,” Hanover said of people who escaped the Holocaust. “That’s why it’s so important to write this book. There’s only so many of these stories left. All of these stories deserve to be told.”

Escaping an unimaginable horror

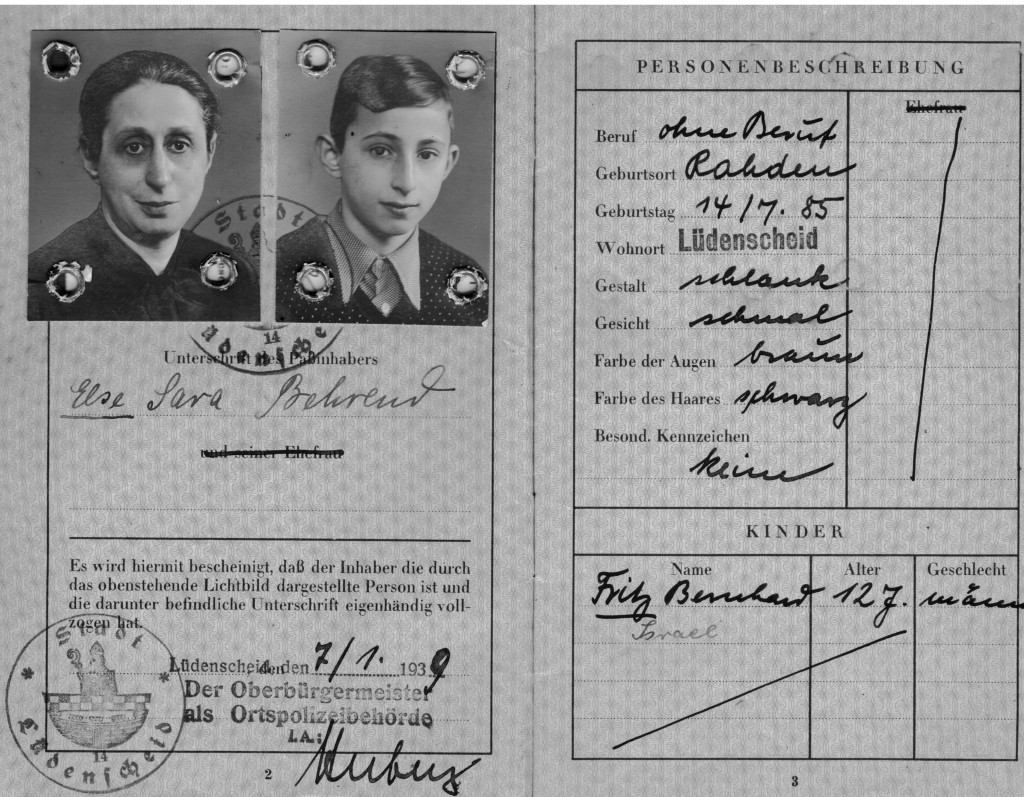

Behrend’s memoir begins at age 6, where he was attending school in Germany just as the Nazi Party was coming to power. Behrend and his family lived in the town of Ludenscheid at the time.

“I wrote down in my head what I remembered about my life starting at age 6, when I went to school for a year or two until such time that Jews weren’t allowed to go to public schools anymore,” Behrend said. “My father found a family in the city of Cologne, and this is where I stayed for two years in order to go to a school run by Jews in the city of Cologne. And then came Kristallnacht.”

Kristallnacht, also known as the Night of Broken Glass, took place Nov. 9, 1938. It’s a night Behrend, who was 12 at the time, remembers vividly.

“Over 500 synagogues in Germany were burned down,” Behrend said. “Jewish stores were plundered. Private homes were entered. Things were thrown out the window. It was terrible.”

“That same night, whatever Jewish males could be found, they would be taken prisoner, put into jail by the Gestapo or the storm troopers would come and transport them to the various concentration camps,” Behrend continued. “My father was put into the concentration camp named Sachsenhausen.”

After three weeks, Behrend’s father was released from Sachsenhausen, but the entire family was stripped of their money and valuables and forced to leave their country in early 1939. The Behrend family boarded a boat named the Iberia to Cuba, where they would await admittance to the United States. The Iberia was the last ship allowed to deliver Jewish refugees to Cuba.

The Behrend family spent 15 months in Cuba before being admitted to the United States. It was in Cuba where Behrend made his first childhood friend.

“I was not allowed to have any friends in Germany because my parents were afraid these young German children were already being educated, the Hitler youth, and they were afraid they were going to harm me,” Behrend said.

“One day, one of the kids came up to me,” Behrend continued. “He was flying a kite, he had a string. He tapped me on the shoulder and he wants to hand me the string. I was happy. I was flying a kite.”

A new life in the United States

When Behrend speaks about his experiences to groups of people around South Jersey, the part he likes to talk about most is when his family arrived in New York City.

Behrend’s family was able to enter the U.S. with help from his Uncle Otto. At the time, refugees could only enter the U.S. if they had an affidavit from a U.S. citizen saying they would take care of the refugee, or if $7,500 was deposited per person into a U.S. bank.

Behrend’s Uncle Otto, who was a wealthy resident of Denmark, paid $90,000, equivalent to about $600,000 today, to allow Behrend and 11 other family members to escape to the United States. Otto also helped his immediate family escape to Sweden before he died just as Germany was invading Denmark.

“You can imagine how much money was spent in order to rescue us from the Holocaust,” Behrend said.

Though the Behrend family was able to escape from Europe, they had to start a new life with practically no money or possessions in New York City.

“We were absolutely penniless,” Behrend said. “We owned nothing. Whatever we had was taken away from us before we left the country, whether it was furniture, jewelry, anything that was worth anything, we could not take with us. We were lucky to get out with our lives.”

Behrend credited organizations such as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the American Joint Jewish Distribution Committee for assisting refugees in getting on their feet. Behrend talked of how his family received an apartment and food for one year so they would get on their feet.

As a teenager, Behrend attended George Washington High School, where he made friends with a few people who went on to be prominent Americans such as former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Fred Westheimer, who would later marry renowned sex therapist Ruth Westheimer.

Coming full circle

Behrend served in the United States Army from July 1945 through December 1946. Behrend’s service began shortly after the Allies defeated Nazi Germany. It was in the Army where Behrend’s background led him to working with captured German prisoners of war.

Since Behrend knew how to speak German, he was given an instructor position where he taught the POWs about democracy. The purpose of the program was the “denazify” special selected prisoners as the Allies began to rebuild Germany.

During his role in the Army, Behrend also worked with a famous German scientist, Wernher von Braun, who was most famously known for his invention of the V-2 rocket, a ballistic missile Nazi Germany used against Great Britain during the war. Von Braun began working for the U.S. Army after surrendering during the final year of the war.

Behrend was assigned to watch over von Braun in El Paso as he performed research in the United States. Von Braun would go on to help develop the Saturn V rocket, which the United States used to launch the Apollo 11 mission to the moon in the late 1960s.

Behrend remarks about how bright von Braun was and recalls one conversation he had with the scientist.

“In his office was this picture,” Behrend said. “All it had was a wagon wheel with the spokes going down to the axle. One day I said, ‘Professor, what is this picture? It’s just a plain old, ordinary wagon wheel.’ He said, ‘Sergeant Behrend, that’s where people are going to live one day up in space.’ I said, ‘Professor, you are just kidding me. No one is going to live up in space.’ He goes to me and says, ‘And you will be alive to see it.’”

“He was an amazing person,” Behrend added. “Very bright.”

Behrend continued to interact with well-known Americans after his time in the Army. Behrend owned an air conditioner and television repair business in Manhattan, where his clients included celebrities such as musical conductor Eugene Ormandy, singer Yoko Ono, author Joseph Heller and singer Carly Simon.

During his adult years, Behrend talks of how he ran into a couple people from his past, others who also managed to escape Europe during the reign of Nazi Germany. Behrend’s memoir shines a light on the new life he and others were able to start following their escape.

Putting Behrend’s life in print

Compiling Behrend’s many lifetime memories was only part of the job for Hanover. The other part was finding someone interested in publishing the 90-year-old’s memoir.

“I looked for a literary agent,” Hanover said. “I thought I had somebody. She said it was good writing, but said she couldn’t sell a memoir. Memoirs don’t sell.”

Hanover thought they might have to self-publish the book until he spoke with a colleague at Temple University, the school where Hanover teaches a journalism class once a week. Hanover was told to try to approach a university press to publish the memoir.

“At that point, I researched and found that Purdue had Jewish studies,” Hanover said. “They jumped on it right away.”

Numerous revisions were done to the book after undergoing scholarly reviews. After years of work, the final version of the book was released on Saturday, July 15.

“The research is not scholarly, but it is his life story,” Hanover said of the completed work. “We faithfully presented his life story as best we could.”

“Rebuilt from Broken Glass: A German Jewish Life Remade in America” is available in both eBook and print form for $29.99. To purchase the book, visit www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/rebuilt-broken-glass-german-jewish-life-remade-america.